Help your striving readers craft written responses to text

Written responses seem to be the trend, including within state assessments. But how do we move our striving readers and writers to a point that they can express their thoughts, support them with text, and discuss them with others?

After all, the purposes of written response include examining, explaining, and/or defending a reaction to text – higher level skills that take time to develop.

1. Awaken their senses of reaction with talking and good context

In this world where we can share a reaction with a click of a heart, thumb, or emoji face, responses have become trite. In other words, students have experience responding on the surface level with an immediate opinion about whether or not they like (or love) something, but they have little chance to analyze those reactions beyond the click.

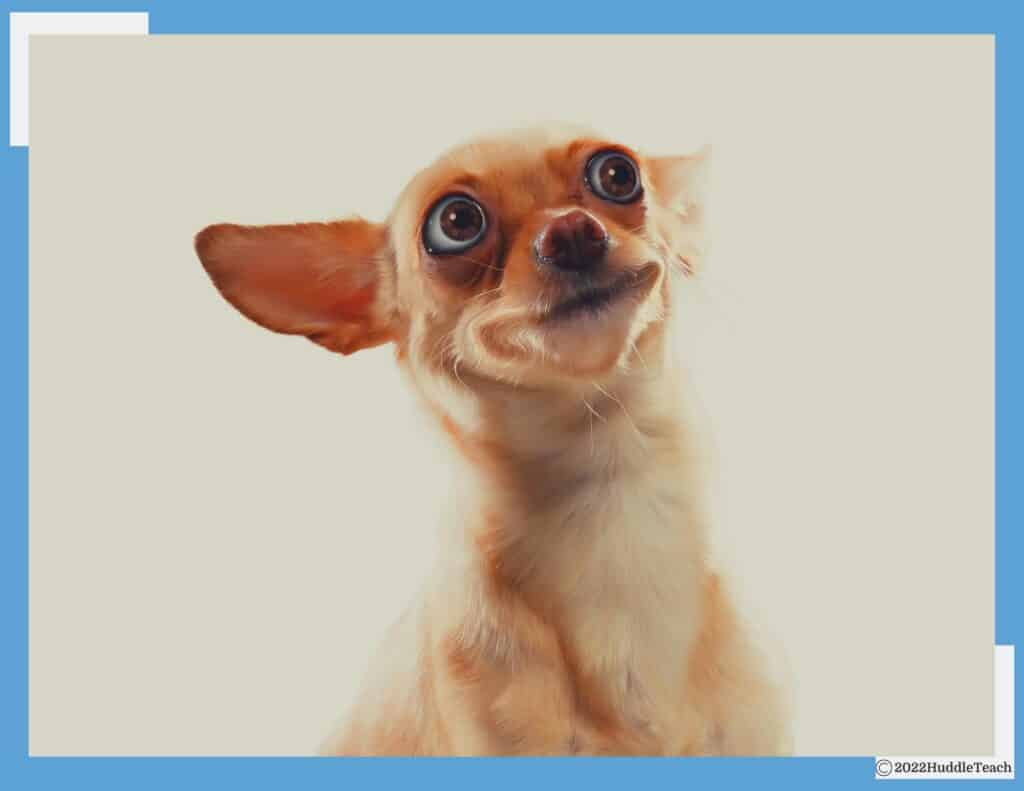

Start by delving into this idea of reacting to photos. This works because visual and auditory skills generally develop earlier than reading and writing skills. Also, photos meet our students where they are to build the skills necessary to move forward.

The key is in the asking! Be sure to discuss WHY students have a specific reaction. Use points within the photo as text evidence to support their reactions. Let them talk about the pictures to solidify this skill.

So much on the internet is meant to shock – and so much in our world is overwhelming – that we wanted a set of pictures that are a bit more benign but offer a chance for reactions. Take a look at them here!

2. Build writing stamina and fluency

When it comes to writing, the scaffold begins with oral language. Once students can speak coherently, they are well on their way to writing coherently, but certainly you can work on the two simultaneously.

When we talk about speaking and writing coherently, we don’t mean in the sense of clear speech or legible handwriting, but more in the sense of communicating ideas succinctly in a logical, related order.

Incorporating quick talks and writes into your classwork – even a few times a week – helps students gain control of their thinking and writing, builds writing fluency and stamina, and develops students’ overall literacy skills. Incorporate feedback and mini-lessons to turn these quick-writes into full writing lessons to best grow your students’ written response skills.

If possible, we recommend Linda Rief’s The Quickwrite Handbook, but in short, this is the routine:

- Set a timer for 2 minutes (work up to 3-5).

- Provide a prompt or give time to free write.

- Stick to the rule that the pencil is always moving on the paper, even if it is to say I’m not sure what to say.

- After the timer sounds, count the number of words written. (This data makes a great bar graph for showing fluency and stamina growth!) Write the number and circle it on the page.

- Have students turn and talk to share their thoughts with each other. Highlighting a favorite line to share helps, too!

- Remember the goal: think and write and think and talk to build deeper skills.

3. Use your words

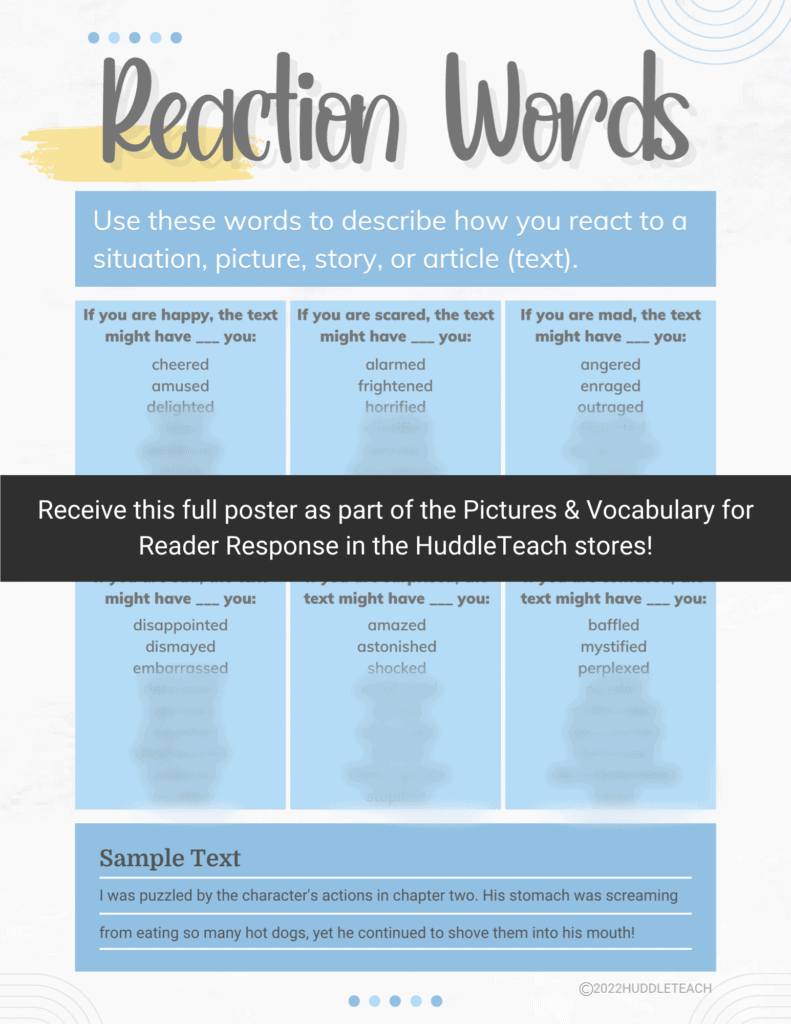

It’s important to remember that reader response begins with the reader! Build students’ reaction vocabularies beyond like, love, sad, mad, awww, and gross to move to the next level.

Take time to teach students higher love

Once you have them talking, move into more writing!

4. Move beyond personal

These are great starts, but students must move to constructed responses to be academically successful. Like all good instruction, this takes planning on your part as well as a degree of modeling, especially for our striving readers and writers.

A planning sheet will help you as you implement more structured writing. While a planning page is not necessary for every reader response assignment, it is suggested to do so until students are more independent in their work. It helps you help them improve!

Remember that reader response begins with the reader, but the conversation with the text is what supports their thoughts. Annotating and using Think Marks are one way for students to have the conversation with the text first, then bring their thoughts to discussion, then to a written piece.

A final word about thinking and written response

One of the most popular complaints between teachers is students’ lack of ability to think…to actually reason with information. While there are many factors contributing to this, we must be careful that we do not take opportunities to practice thinking and make them into convenient worksheets – for long, anyway!

Formulas are a means to an end. In and of themselves, they won’t produce thinkers – the ultimate goal of reading and writing. If you must start with RACE, ACE, or CER, of course, do so! Just know it’s an okay place to be, not an okay place to stay, as you develop your thinkers and writers!