Why the hats, mountains, and roller coasters don’t tell the whole story

Earliest Stories

Our youngest children, from birth to kindergarten, often experience stories told as a sequence of related events. Think of titles like Brown Bear, Brown Bear and Goodnight Moon. These books are important for learning language, pattern, repetition, and sequence. If you were to draw a diagram representing the movement of information in the text, it would most likely be a set of arrows or simply a straight line – if anything at all. (Although I do love the circular cause-effect pattern of If You Give a Mouse a Cookie and use it even with older students to discuss plot lines.)

Early Elementary Years

Then children enter school and more robust stories become more popular. The Day the Crayons Quit series, I Don’t Want to Be a Frog, and everything Pete the Cat introduce young students to problems in a story. Teachers support understanding by creating BEGINNING-MIDDLE-END activities. What a perfect way to begin discussing characters, setting, problems, and endings! Long before there were Common Core Standards, teachers were leading students through trifold-construction-paper retellings of fabulous stories!

In fact, Common Core Standards lists the expectation, “Describe how characters in a story respond to major events and challenges” (using that word for the first time) in second grade (CCSS.ELAR-LITERACY.RL.2.3). Texas lists the expectation in first grade as, “…describe the plot (problem and solution) and retell a story’s beginning, middle, and end with attention to the sequence of events” (110.12.1.b.9.A).

Mid-Elementary Years

As students age, so do the expectations for understanding character and conflict. In CCSS for third grade (Texas TEKS for second), more emphasis is placed on conflict, character traits, and motivation. It’s the right time to begin teaching the plot diagram in relation to these elements. Students are more developmentally ready for this level of analysis and texts are becoming more complex.

No conflict,

No story.

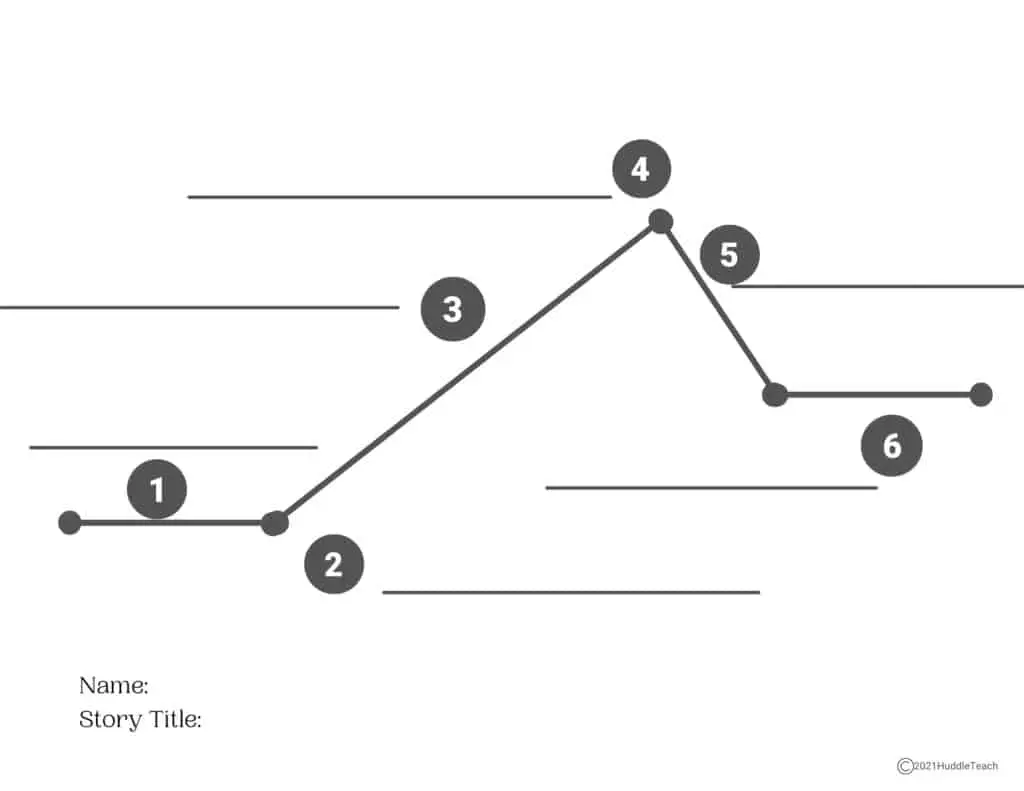

How the Plot Diagram Represents Growing Conflict

Enter the beautiful plot diagram! This work of art, developed from the original Freytag’s Pyramid for plot structure of drama, has found a permanent place in story analysis. Its goal is not just to map the sequential events occurring across a story, but to outline the occurrence and escalation of conflict to a breaking point and through to a resolution or ending.

The plot diagram includes these major sections:

- Exposition – The main characters and setting are introduced (“exposed” to the reader). This typically occurs in the beginning of the story, but character lists may grow and settings may change throughout.

- Inciting Event (or Inciting Incident) – The main conflict is revealed! Sometimes this occurs on the first page as a glorious hook into a story, or it occurs shortly after the introduction of the characters and setting.

- Rising Action – The conflict escalates. The key here is ESCALATION. This is not just a series of events, but rather an increase in the intensity of the action. The rising action is the longest part of the story because conflict is growing. It’s the tension that keeps us reading! Just think – if the tension were to be broken in the middle of the book, would we ever finish reading it? Maybe only if we REALLY cared about the character. Otherwise, it just drags on.

- Climax – The point of greatest tension. Some teachers describe it as the “most exciting part.” As a student, I had the most difficult time understanding that concept. For my students, I describe it as “the beginning of the end,” or the event that made the end of the story possible. It could be something subtle, but it is what caused a turning point in the conflict. (Cliff hangers end here.)

- Falling Action – The effects of the climax. The parties of the conflict begin to resolve their issues. This is a path to the resolution or conclusion of the story.

- Resolution / Conclusion – This portion tells how the conflict is solved or comes to some other satisfying ending. Characters who have solved a problem or survived a conflict are typically better for it, coming out stronger or wiser.

So Where Does it Go Awry?

This short video explains where the transition from beginning-middle-end to plot diagram goes a little off the tracks:

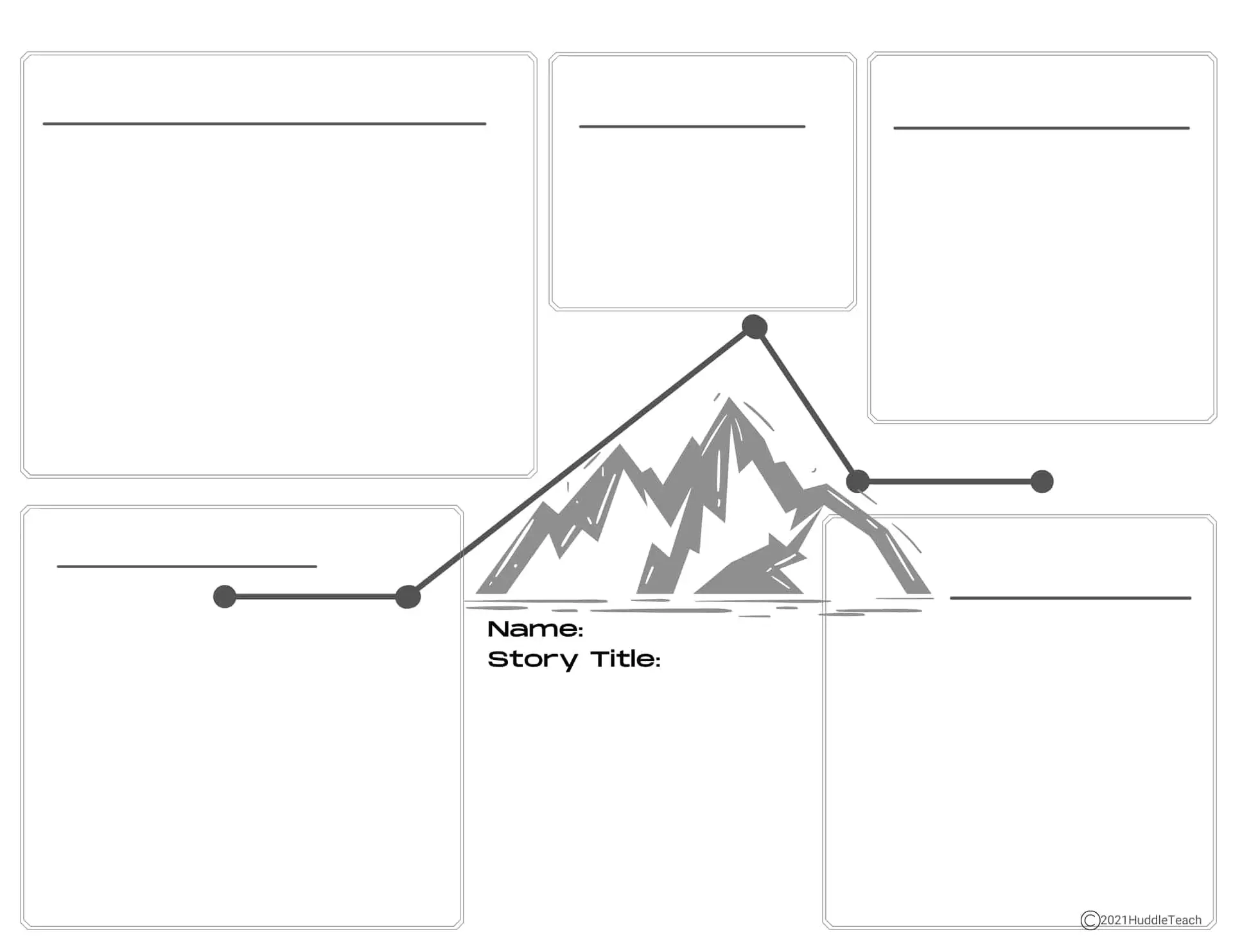

So What Plot Diagrams Can Be Used Instead?

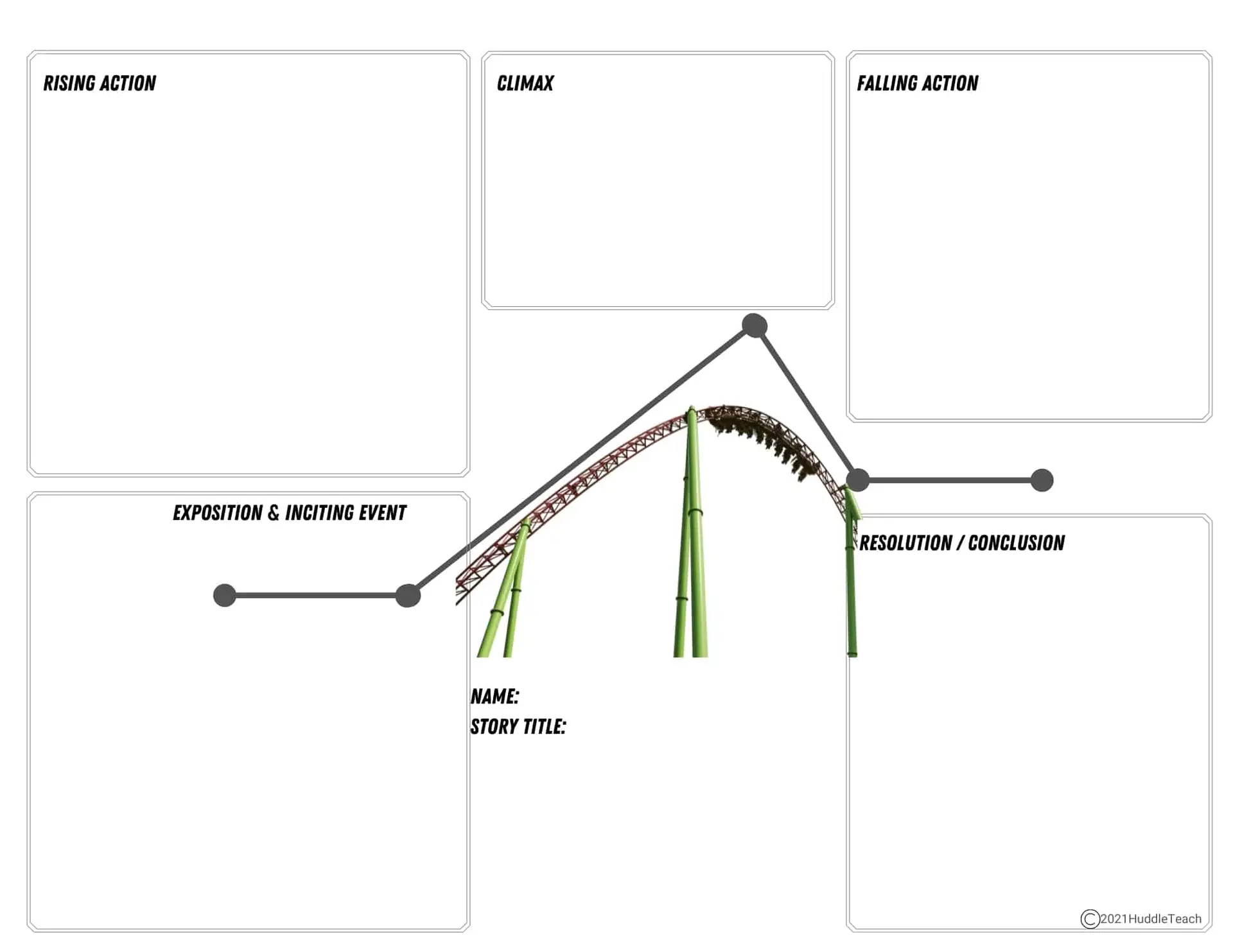

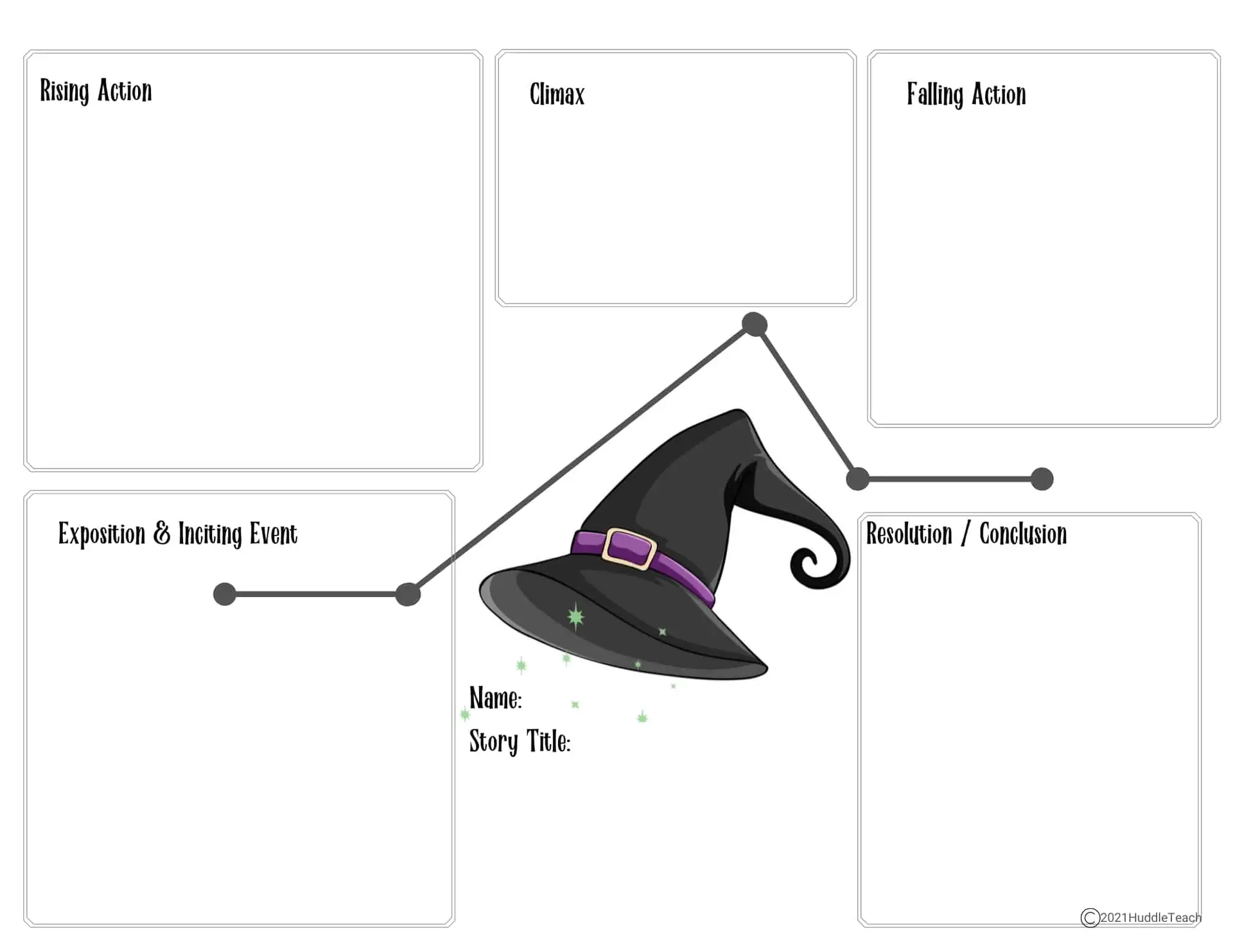

Plot diagrams with tilted rising action and a climax closer to the resolution and a shorter falling action make better plot diagrams. Check out these in the HuddleTeach store and on Teachers Pay Teachers. The set includes three days of lesson plans, interventions that help students understand the role of conflict in story, and over 100 pages of materials for you! Included are two sets of plot diagrams. Each set is the same with the exception of the size. We think that when working with striving readers, bigger is better. The 11″X17″ laminated is perfect for working through stories together. Legal and letter size are also included. There are plot diagrams with inciting event and without. Some have witches’ hats, mountains, a roller coaster, or nothing! Use what you need! There are 20 variations in each size for use all year!

Is This Where Plot Diagrams End?

Plot diagrams have evolved past this diagram to include nonlinear plot lines (flashbacks, foreshadowing, etc.) and a completely different pattern of story: The Hero’s Journey. But more on that another day!

Watch for more resources to help you teach plot!

Our HuddleTeach store is always growing! We’ve added plot line manipulatives to help our students understand even more! Check them out in the HuddleTeach store or on Teachers Pay Teachers.

Also, join our HuddleTeach community on social media, or sign up for our weekly newsletter, full of resources, information, and access to our freebie library!