Understanding the relationship of ideas in text

Beginning Early

Older students have been learning the underlying concepts necessary to understand nonfiction text structures for years. Take the hula-hoop sorting activities in kindergarten, preparing students to discuss compare / contrast relationships in later grades. Sequencing a story in primary grades with felt board characters prepare students for sequencing text in older elementary years.

Then in grades 1-3, students learn how text features like headings, graphics, and bold print guide the relationship of ideas. Graphics, such as charts and diagrams, are especially helpful as models of these relationships. Students are completing the next step in being ready to analyze and illustrate nonfiction structures within text.

This hands-on groundwork – and all its related activities – should create later readers who can verbalize the relationships of ideas within informational text. So when we have older students who cannot do this, we have to wonder why.

The beauty of graphic organizers – and the danger

We know that mental models help move information from short term memory into longer term memory. It has been widely proven that graphic organizers, such as the Frayer Model, have positive effects on students’ learning. Beyond vocabulary, many subject areas use graphic organizers to guide understanding. In fact, they are often a staple in English and social studies classes, written into purchased curriculum components.

Unfortunately, some of these graphic organizers became worksheets to be completed rather than a tool for guiding understanding. They lacked the implementation of the thinking process. (Read more about this with plot diagrams on this post.) Or perhaps the student was not quite ready to mentally own the model and instead simply copied the organizer as teachers completed it. Either way, students did not internalize the critical thinking skills.

When children have a broad base of experience with informational language

and informational forms,

those texts and language patterns become familiar…

and strategies become habits.

Linda Hoyt, 2005

Categories of comprehension

Beginning with fourth grade, standards specify that students should be able to identify relationships of ideas within text. In other words, they should be able to explain if details are compared and contrasted, if a description is being made, if something is occurring in a sequence of steps or time, etc. To build the ownership of this skill, instruction should follow this continuum:

- Literal – use key words to identify the relationship of ideas

- Interpretive – make inferences about the relationship of ideas, even with few key words

- Critical – distinguish important from unimportant information and apply knowledge of relationships

- Creative – develop mental models to represent information in the text

The difficulty happens at the transition points for each stage. Each transition requires expert teaching, modeling, and scaffolding for success.

Nonfiction text structures to teach

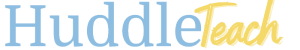

First, decide which nonfiction text structures to intentionally teach. Most popular are:

- description

- compare / contrast

- cause / effect

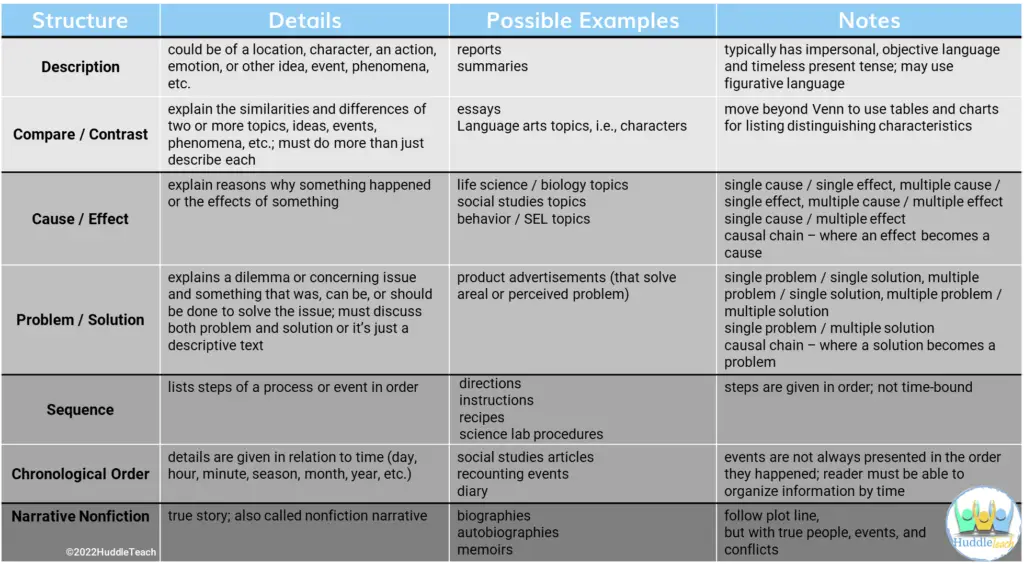

- problem / solution

- sequential / chronological order

For secondary students needing more support, though, sequential and chronological order can be separated, and nonfiction narrative (or narrative nonfiction) can be added:

Common confusions within text structures

It is important to teach older striving readers that text using chronological order may have information presented out of sequence. Students must be able to analyze the dates and put them in order of time.

Text that uses sequence – or steps – typically has information presented in order. The information is not time-bound. For example, a recipe will not tell the reader to “stir at 3:00pm.” Neither will it say, “…and before that, mix in the eggs.”

Narrative nonfiction – or nonfiction narrative – is another confusing point for striving older readers. Reviewing the plot diagram is helpful with emphasis on the point that all things are true or real: characters, setting, and events.

Move through the categories of comprehension to independence

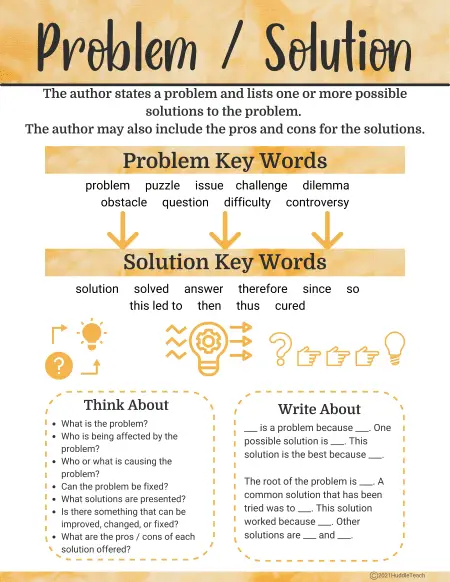

Students need ample experience with informational text. Using anchor charts, posters, and notes like these build mental models:

Then, sort and review all structures, like this. These types of activities support the Literal and Interpretive categories of comprehension.

Moving into deeper thinking

Next, move to using passages with mixed structures for close reading practice. Tackle these with students, discussing the relationships of ideas within the text as you go. Do not underestimate the amount of modeling and discussion in this phase as this is a key transition point. This work moves students into the Critical category of comprehension. Work together to extend this thinking by creating models that display the complex relationships. These models may include several of the basic structures put together to form a cohesive picture of the ideas.

Turn over responsibility

Continue increasing text difficulty as students take more control over explaining and illustrating the relationship of the ideas presented in the text. Before you know it, students will be doing the critical thinking in difficult passages on their own! When they can successfully do this, they have reached the Creative category of comprehension!

Ratchet the level of difficulty by following close reading activities with passages on the same topic with higher Lexile levels, or keep the same difficulty and provide passages for which students do not have a lot of background knowledge. Ask students not just to answer any provided questions, but to create a model that shows the relationship of the ideas presented. As you have modeled and scaffolded the idea of using many structures to represent information in a passage, they will know just what to do!

These task cards and passages from sites like Newsela help!

What activities have you found helpful as you build this skill in students?